~ CREATIVE SOAPMAKING ~

June

Cucumber Soaps

Low Temperature Soapmaking

Contents

Cucumbers in Soapmaking—Why?

Avoiding Burned Cucumber Odor

Basic Cucumber Soap and Variations

Cucumber and Apricot Soap

Cucumber and Avocado Soap

Color—Natural and Artificial

Hardness

Does Cucumber Accelerate Trace?

What Would I Do?

Low Temperature Soapmaking

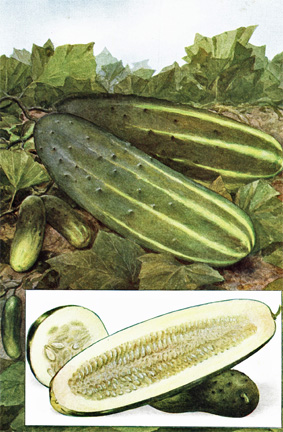

Cucumbers in Soapmaking—Why?

Cucumber has long been regarded as beneficial for the skin. According to the Cambridge World History of Food, cucumbers have been used at least since the nineteenth century in soaps and other cosmetics.

They're believed to improve the complexion, soothe the skin, and fade freckles. Cucumbers do seem to be somewhat astringent, and cool cucumber is pleasant on the skin on a hot day.

Occasionally, they're even claimed to treat more serious skin conditions. As soapmakers, we know we can't make claims of that kind. Whatever the benefits of raw cucumber, they may or may not still be present in cucumber soap.

Probably the main advantage of cucumber soap is its pleasant texture and appearance, which give it good marketability. It makes an appealing soap, especially with green flecks of cucumber peel in it.

Avoiding Burned Cucumber Odor

As I looked at recipes and comments about making cucumber soap, I stumbled across one that occurred over and over: People said the lye burns the cucumber and produces a nasty odor. Some said the odor fades, others said it doesn't. But I started wondering if it would work to treat cucumber, and possibly other fruit and vegetable soaps as well, the same way we treat milk soaps to avoid burning—freeze the liquid in ice trays, and sprinkle the lye onto the cucumber "ice cubes."

It worked perfectly. I'd strongly recommend freezing anything that's likely to burn when lye is added to it. You get better soap, with less likelihood of a "volcano." (More about that below.)

Since I was using frozen liquid anyway, I decided to try a 50-50 mixture of cucumber and yogurt in some of my soaps, in addition to making some with only cucumber juice and/or pulp as the liquid.

Basic Cucumber Soap and Variations

Since there were so many questions about how to work with cucumber, I decided to start with a basic recipe. I branched out a little after a few batches, but this basic recipe is the main one I used, given here with a few variations.

21 ounces (595 grams) olive oil

9 ounces (255 grams) coconut oil

9 ounces (255 grams) frozen cucumber juice, puree, or mixture of cucumber and another liquid

4.2 ounces (121 grams) lye, bead or microbead

Cucumber Yogurt Soap

Half the liquid was frozen cucumber puree, including very finely minced peel. Half was frozen plain yogurt. I mixed the two before freezing. This formulation made a nice looking beige soap with green flecks. Lots of excellent lather, bubbly and creamy. The flecks of peel are slightly exfoliating—not as much as cornmeal or coffee grounds would be, but noticeably a little rough.

Cucumber Puree Soap

Part or all of the liquid was frozen cucumber puree. Puree in different batches was made both with and without the peel.

Olive/coconut soap with whole pureed cucumber

Cucumber Juice Soap

All the liquid was frozen cucumber juice. Juice in different batches was made both with and without the peel.

Cucumber Soap with French Green Clay

I added two teaspoons of clay to the basic recipe, using the juice from peeled cucumbers as the liquid. I thought the soap might be green, but it was pale beige. However, some green clays are green enough to affect final color, so if this is what you want in a clay soap, ask around and shop around.

Cucumber and Apricot Soap

15.9 ounces (451 grams) apricot kernel oil

3 ounces (85 grams) shea butter

2.1 ounces (59 grams) castor oil

9 ounces (255 grams) palm kernel oil flakes

10.6 ounces (300 grams) frozen cucumber juice

4.2 ounces (119 grams) lye

Cucumber and Avocado Soap

6 ounces (171 grams) avocado butter

9 ounces (255 grams) coconut oil

15 ounces (425 grams) olive oil

10 ounces (283 grams) frozen cucumber puree or juice

4.2 ounces (119 grams) lye

I used a mixture of frozen puree and juice in my batch.

Color—Natural and Artificial

The natural color of my cucumber soap is pure white when it's made with juice of peeled cucumbers and medium green olive oil.

Soaps with juice from peeled cucumbers, olive oil, and 76-degree coconut oil are light beige unless they're warmed during setting. Those darken somewhat. Including the peel with the juice also makes a darker beige soap, not green.

Made with cucumber puree, soaps might be either beige or pale green. Regardless of the main color, if the cucumbers aren't peeled, the soap has green flecks.

In my batches, the only green soap was the one with cucumber I pureed in a food processor. When I pureed the cucumber with the stick blender, I got beige soap with green flecks.

In the batches I tried to swirl, I used green chrome oxide for the color. It didn't bleed and was quite stable. However, in the darker batches, the contrast wasn't enough for a particularly good effect. For best results with color effects, use juice from peeled cucumbers and don't let the soap gel. Some of my swirl batches traced and set too quickly for swirling to work well.

Hardness

Many of my cucumber soaps tended to be soft. I suggest making cucumber soaps with an oil mix that has at least a medium hardness value, and with superfatting at no more than 5%.

Does Cucumber Accelerate Trace?

I'd heard that cucumber fragrance, or cucumber melon fragrance, accelerates trace. None of the ones I tried actually did. Neither did the cucumber itself.

What Would I Do?

If I were making cucumber soap for myself, I'd use the strained juice rather than pulp. I preferred the texture of those soaps. Or I'd use a 50-50 combination of yogurt and strained cucumber juice for the liquid.

If I wanted the green flecks of cucumber peel, I'd process the peel in a food processor with water, drain it, and add it to my soap at trace.

For making juice, I preferred the results I got using a heavy-duty vegetable juicer to what my food processor was able to do. I believe almost any fruit or vegetable juice could be used in soap this way, although I have tried only a few. For any organic liquid such as vegetable juice, I'd work with it frozen.

Since vegetable juices tend to be acidic, I'd use them in soap formulations with good hardness and would not have my liquid exceed 30% of the weight of the fats. I would not formulate for superfatting above 5%.

For more thoughts about developing your own recipes, see October.

Low Temperature Soapmaking

Throughout history, soap has mostly been made hot. In fact, soapmakers were known as "soap boilers." Like many professions, soap boiling had its patron saint—Saint Florian, who is also the patron saint of firefighters.

Saint Florian's Gate, Poland

As far as I've been able to learn, high temperature work was the rule both for family and commercial soapmaking until around 1940. At that time, companies who manufactured lye began to market it differently for private soapmaking, which was falling out of fashion. I've found the term "cold process soapmaking" in an undated lye company pamphlet that appears to be from about 1940-1950, based on the illustrations.

What we call hot process soapmaking for craft soapmakers today may take one of a number of forms. The soap may be brought to trace without heat, then cooked in a slow cooker. Or it may be brought to trace without heat, poured into a mold, and "baked" at low temperature in an oven. Or it may be heated prior to trace.

Cold process isn't actually cold. It may be done at anything from room temperature to about 120°F (49°C). Typically, the soap is poured into molds and kept at room temperature until it sets, then unmolded, sliced, and set aside for curing.

What are the advantages, hot or cold? Hot process is ready to use almost immediately, is kinder to additives, and requires less fragrance/essential oil.

Cold process is faster (not counting curing time), may be easier to mold, and may have less fumes and require less direct supervision.

Both methods also have disadvantages. Some soapmakers use only one, some use both, depending on the ingredients they're using.

Milk soapmakers came up with a special technique I refer to as Cool Technique in my book Milk Soapmaking. In this method, the soapmaking liquid is frozen. Lye is trickled onto it, and the heat from the dissolving lye gradually melts the ice. The soap is mixed normally and may be refrigerated or even briefly put into a freezer after pouring to keep the heat of saponification from scorching milk or other fragile ingredients.

Like other methods, Cool Technique has its advantages and disadvantages. Preventing scorching is its main advantage. It also reduces fumes—a lot.

But if you count freezing time, it takes longer. Also, Cool Technique soaps may be more likely to get the chalky white deposits known as soda ash (For ideas about preventing and removing soda ash, see November.)

If you make many different kinds of soap, it's probably an advantage to consider all techniques, and to be skilled in all.

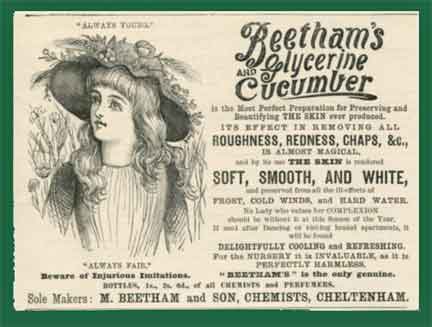

Nineteenth-century trade card promoting the use of manufactured lye for soapmaking. We don't know how the soap was made, but availability of a standardized manufactured product would have been a major advantage over homemade lye.

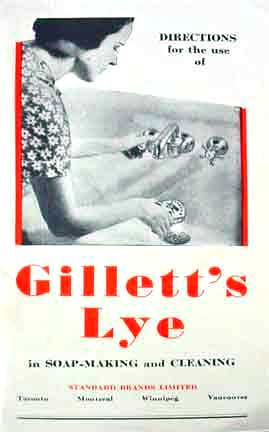

Pamphlet for use of Gillett Brand lye in home soapmaking. It's undated, but based on the dress and hairstyle of the model, I'm guessing it was published around 1940–1950. It uses the term "cold process soapmaking."