~ CREATIVE SOAPMAKING ~

August

Herbal Soaps

Working with Trace Accelerants

Contents

Herbs in Soapmaking—Why?

Botanicals in Soap

Infusing Oils with Herbs

Herb Teas

Herb Essential Oils and Fragrances

Botanicals and Lye

Basic Herbal Soap and Variations

Coconut Almond Soap with Herb Tea

Triple Calendula Soap

Tomato Basil Soap

Lavender, Shea, and Almond Soap

Working with Accelerants

What Would I Do?

Washington State lavender farm

Herbs in Soapmaking—Why?

Almost everyone likes herbs. How well they work in soapmaking is another matter.

There are different ways to go about it.

Infuse the oils with fresh or dried herbs. There are several ways to do this, using either heat or time to transfer the herb fragrance to the oil.

Make an herbal tea and use that as your liquid.

Herb essential oils are available for a few herbs. They vary in strength, holding power, and attractiveness as scent. Some are less suitable for solo use than for adding complexity in blending.

Herb fragrances don't produce an all-natural soap. In my experience, some also are unsatisfactory as scents, unless you want soap that smells like spaghetti sauce. Fragrances like Herbal Essence don't smell so much like food but are "green" floral blends that don't reproduce any particular herb.

Botanicals in Soap

1907 ad for herbal soap

Pay attention to the properties of herbs when designing your soap. It may not make much sense to design a soothing chamomile or calendula soap and then put a lot of scrubby material in it. Or to put soothing herbs into an oil mixture that's more cleansing than emollient. Look at the whole picture.

It may look nice to put a lot of botanicals into a soap, but that stuff is going to end up in your bathwater, or at least in your drain.

One leaf that supposedly works well to give a green speckle appearance is passionflower leaf. This is available in tea form. (Note: I haven't been able to find just the leaf. Passiflora tea turns out to be the flowers). Another is dried parsley.

When you've decorated the top of a loaf or block of soap with botanicals, cut from the bottom up when you cut it into bars. If you cut from the top down, you'll drag the botanicals down through the soap.

Infusing Oils with Herbs

Mint, from old herbal

You'll come across many different suggestions for doing this. Almost all are intended for cooking or salad oil use, and most work well for that.

After a number of experiments with infusing oils for soapmaking, I only found one method that worked well for me. That is to add commercial dried herbs to oil and leave it to steep in a cool dark place for a fairly long time—a month or more. When I tried infusing oil with fresh or home-dried herbs, I got mold.

I've read that herbs can be infused by simmering the herb and oil mixture in a slow cooker. For me, this produced scorched oil.

I've also read that it's possible to infuse oils with herbs in much the same way you'd make sun tea—put the mixture into a clear glass jar and set it in the sun for a while. I believe it, but my part of the world doesn't get enough direct sunlight to make this practical, so I didn't test it.

Herb Teas

All kinds of herb teas are available—mostly in tea bags, in my supermarket, but some are packaged as loose tea. Chamomile, mint, lavender, and many others are easy to find. I wondered whether herb teas would give any scent or color to the finished soap, and if they did, how long it would last. I also wondered if herb teas would affect the feel and texture of the soap.

With all the choices available, there was no way to test them all, but I selected a few for the experiments here.

Herb Essential Oils and Fragrances

Common thyme, from a old herbal

Essential Oils

An essential oil is a volatile oil that contains the aroma compounds from a plant. EOs are usually steam-distilled, solvent-extracted, or cold-pressed. I've seen articles on "making your own essential oils" that describe infusing oils with herbs, but it's not the same thing. Essential oils are much more concentrated and fragrant than infused oils.

Lavender and rosemary are popular. Bay laurel, catnip, sage, fennel, chamomile, mint, marjoram, basil, and thyme are also available. When using herbal essential oils, it's wise to research possible medicinal effects, since they're very concentrated. Responsible vendors may warn about use of specific essential oils during pregnancy, or with certain medical conditions, but it's a good idea to do your own investigating—many of the drugs in our modern pharmacopeia originated with herbs and other plants.

Some herb essential oils accelerate trace dramatically, and not all vendors mention this in their catalogs. Other essential oils seemed to retard trace. Ask at the time of purchase about an essential oil's behavior in CP soap, or begin with a very small test batch, or both. Test a blend in any case, because a combination of essential oils can have an effect that none of them do by themselves. The scent of a mixture in the finished soap may also be different from what you'd expect, judging from before they're saponified.

Some herb essential oils are quite expensive. Others are much more affordable. Quality varies a lot from one vendor to another. When you're shopping for herb essential oils, first buy the smallest size possible, especially if the EO is a pricey one, then decide whether it's worth the money. Once a vendor gives you a specific product you like, stick with that.

I made one blend of herb essential oils that was a standout: 43% bay, 21% sage, 7% thyme, and 29% rosemary. Be warned, though: It accelerates trace. (Both bay and thyme EOs are accelerants). See suggestions below for working with accelerated trace.

Old medicinal herb boxes, shown with a selection of herbal soaps. Uses are listed on the sides of the boxes—many herbs are effective medicines.

Fragrance Oils

Fragrance oils are artificial, of course, so I'll only touch on them in this discussion of herbal soaps. I've tried a few herb fragrances that are billed as duplicating essential oils. I didn't think any of them were convincing. Some "herbal" fragrances are really floral fragrances with "green" notes. They're pleasant, but not the pure scent of herbs.

Coconut-Almond Soap scented with herbal fragrance oil

Botanicals and Lye

Botanicals—actual plant material such as lavender buds—may be affected by lye.

However, not all the common information about this is reliable. When I began researching the effect of lye on botanicals in soapmaking, I ran into so many contradictions that I decided to do a little testing myself.

For instance, I found contradictory statements about adding dried mint leaves to CP soap. Some said the leaves turn black—that the best way to get the effect you want is to use dried parsley leaves, which remain green. Others said that mint is one of the few leaves that stays green. Yet another source said they "bleed"—and I wasn't sure what that meant.

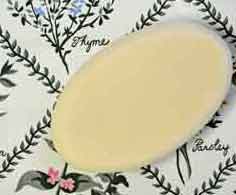

Here are my test soaps with mint and parsley:

These soaps were made from the same basic recipe, given below. Both were scented with mint essential oil. The one on the left has dried mint leaves from an herbal teabag. The one on the right has culinary dried parsley.

Equal amounts by volume were added, but the mint was much finer, so there's a big difference in actual density, and probably in weight as well.

At first, the mint in the soap—though a duller green than the parsley—was the same color it was in the teabag. But after a few hours, the edges of the mint soap developed rusty brown spotting. This is apparently what "bleeding" meant! And the color spreads and darkens as the soap is used.

For a second try, I made mint tea with one of the teabags, squeezed out the leaves, and used them damp. I mixed them into the soap at trace, then poured into molds.

The rusty staining hasn't been completely eliminated, but there's much less. (It shows more in this photo than on the actual soap bar.) However, in use, it increased.

If you want green specks in the soap, with no risk of "bleeding," parsley is preferable—at least at first. In use, though, the parsley flakes harden, become scrubbier, and darken.

Calendula and a few other botanicals don't change in soap.

You can also avoid color change by applying the botanicals to the surface of the soap after pouring. If you do this with soap in a log mold, your addition will wind up all on one side of your bars. With tray or individual molds, it will cover one of the bar's larger surfaces. Either way, fill the mold slightly below the rim and press the botanical material into the surface gently as the soap is setting. (Of course, while doing this, you'll still be wearing gloves!)

Whether you're using a botanical throughout the soap or only on the surface, test a bar in use—sink, shower, and bathtub—before marketing it. If a soap is pretty but requires cleaning the tub every time it's used, you won't get many repeat customers for it.

Since there are obviously many more botanicals than I'm able to test, I recommend you experiment with them yourself, trying very small batches before going full scale. Once you've found a material, texture, and quantity you like, you're set.

Basic Herbal Soap and Variations

Here's a recipe you can use as the basis for an herbal soap. Just add the herbs, in whatever form you choose.

8 ounces (226 grams) shea butter

10 ounces (284 grams) coconut oil

12 ounces (340 grams) grapeseed oil

9 ounces (255 grams) water or other liquid

4.1 ounces (118 grams) lye

Two Basic Herbal soaps. The one on bottom was scented with sage essential oil, the one on top with a blend of fennel, lemongrass, and rosemary. No colorants were used—the difference in color is due to the colors of the EOs.

Olive Oil Variation

Replace the grapeseed oil with olive oil. Increase the lye to 4.2 ounces (121 grams). I was especially pleased with this variation. It had great lather, both bubbly and creamy.

With this mildly scented infused olive oil, neither the rosemary color nor its fragrance remained in the finished soap.

Lavender Cucumber Variation

Building on my June project, I decided to use frozen cucumber juice for the liquid. Use lavender essential oil, or a blend of herbal essential oils with lavender dominant. I also experimented with dairy butter as one of the fats.

Made in a block mold, this soap developed a bull's-eye at the center. If smooth color is important, make soaps with fragile ingredients like butter or cucumber juice in tray molds or individual molds.

I found dairy butter difficult to work with. The texture of the soap was superb, but some batches developed an odd odor, which is why I didn't give a recipe. It was particularly noticeable in combination with lavender essential oil. Substituting ghee for butter did not solve the problem.

Coconut Almond Soap with Herb Tea

Chamomile plant, from old herbal

21 ounces (595 grams) almond oil

9 ounces (255 grams) coconut oil

9 ounces (255 grams) frozen herb tea

4.3 ounces (123 grams) lye

The herb tea seemed to have little effect except for color, but the color was uneven. The blotchiness might not be a problem in a soap with leaf "speckles." It does show in a plain soap.

Chamomile Tea Variation—Neither the fragrance of the chamomile tea nor the color survived saponification. Slow to set, slow to cure. Beautiful lather.

Mint Tea Variation—When the lye was added to the tea, the liquid turned bright red. The color remained until the soap was poured into the molds—as the soap was setting, it faded to tan and then to a slightly blotchy yellow. It had a very faint mint smell at first, which quickly disappeared.

Tea soaps, mint (left) and chamomile (right)

Triple Calendula Soap

12.6 ounces (357 grams) calendula-infused sunflower oil

9.9 ounces (281 grams) palm kernel oil flakes

7.5 ounces (213 grams) shea butter

9 ounces (255 grams) water or calendula tea

4.0 ounces (114 grams) lye

Ground calendula (optional)

Calendula petals to decorate (optional)

Grind calendula flowers to add at trace if you want a scrubby soap. The amount would depend on how much "scrub" you want, but don't use more than four teaspoons of the ground petals for this amount of base oils. You can also use whole calendula petals in soap, instead of the ground petals. Soak the powder or petals in some of the base oil before using.

To make calendula tea to use for the liquid, pour boiling distilled water over calendula petals and let steep. Again, start with more than you need, to make up for waste. Strain, freeze, and use frozen as you would with milk soap.

To decorate the surface of the soap, first fill the molds slightly less than full. With your gloves still on, press calendula flowers into the exposed face of the soap as it's setting.

Tomato Basil Soap

10.5 ounces (298 grams) coconut oil

4.5 ounces (128 grams) avocado butter

11.4 ounces (323 grams) almond oil

3.6 ounces (102 grams) olive oil

9 ounces (255 grams) tomato juice, frozen

4.3 ounces (124 grams) lye

Sweet basil essential oil

I used juice I'd made myself in a juicer. Not sure if canned or bottled tomato juice would give the same results.

Sweet basil essential oil is very strong. If using it alone, you'd want less than an ounce for this amount of soap.

The soap was slow to trace, slow to set. This might be a good choice for soaps with special effects, where you need some time.

When the bars were about half set, I gently smoothed dried parsley flakes into the top of the soap.

If you use fragrance oils, you could add one of the tomato leaf oils to this one. Or blend with one of the citrus essential oils. Or for a kitchen scrub soap, add lemon or orange peel powder.

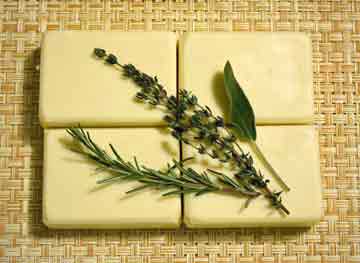

Lavender, Shea, and Almond Soap

10.5 ounces (298 grams) almond oil

10.2 ounces (289 grams) coconut oil

9.3 ounces (264 grams) shea butter

1.6 ounces (45 grams) lavender essential oil

9 ounces (255 grams) light cream or half-and-half, frozen

4.3 ounces (122 grams) lye

Lavender buds to sprinkle on top, if desired

The lavender buds on the surface are pretty, but they do dry out and become brown in time. I wouldn't add them to another batch.

Working with Accelerants

We say that certain materials accelerate trace, but that's only part of the picture. They accelerate everything—trace, setting, and the rate at which the soap's pH drops to a usable level. In the process, they generate a lot of heat, even after the soap is poured. So you not only have to avoid the proverbial "soap on a stick," you also have to think about "volcanoes," scorching of oils or other ingredients, or cracking as the soap sets and cures.

You need to consider both the starting temperature and the way that heat can build up after the soap is poured. Saponification generates heat all by itself, so the soap can get hot on its own after you pour it into molds.

I avoid fragrance oils that accelerate trace, but some essential oils do, too, and if you want their scent, you have to learn to work with them. Here are a number of pointers for working with accelerants. Don't worry—you won't try them all in the same batch! They're offered as ideas to consider—not all personally tested by me.

Work cooler. Use frozen liquid and/or chilled liquid fats.

Let melted solid fats cool as much as possible. One way to do this is to mix them with the liquid fats. The whole mixture is less likely to solidify at room temperature.

When working cold, avoid using a high percentage of hard fats, as false trace is possible if fats congeal before they're emulsified.

Increase liquid. My recipes have water or other liquid at 30% of oil weight, but liquid can be increased to as much as 38%.

Don't use fragile liquids like milk that can't take higher temperatures.

Avoid using honey, sugar, or sugar-containing liquids such as fruit juice for part or all of the soap's liquid.

Avoid using alcoholic liquids.

Use slow-tracing oils such as olive oil. Avoid oils such as castor that accelerate trace by themselves.

Use less of the trace-accelerating essential oil, or combine it with others that retard trace or don't affect it.

Keep quantities down. The more soap you make at once, the more heat is generated, even normally. With an accelerant in the mix, it's easy to generate too much heat.

Use tray molds or individual molds to prevent heat buildup after pouring.

Use molds made of a material that transfers heat quickly. Silicone or plastic would be good. Wood molds retain heat, and are less desirable.

Don't insulate the molds.

Hand stir, at least part of the time.

Mix the accelerant into the soap after pouring. This would be easiest in a silicone block mold or loaf mold—it's best to use one with smooth surfaces rather than a pattern or ripple in the bottom, since it's harder to stir quickly and thoroughly in a patterned mold. To do this, mix the essential oil or other accelerating ingredient with a little of the base oil and set aside. Mix other ingredients as usual until the soap is well mixed but not yet at trace. Pour into the mold and add the accelerant mixture. Hand stir until trace is reached. Stir thoroughly and carefully, paying special attention to edges and corners. (A spatula is useful for this.) Since the block mold shape will retain heat, this idea should probably be combined with cooling the mold as the soap sets.

Refrigerate molds after pouring as we do with milk soaps.

If you're using more than one mold, don't place them close together after pouring—this makes the soap retain heat, and can cause a "volcano." Set them down with air space around them.

Mix a small amount of one of the liquid fats in the soap with the trace-accelerating essential oil. Add after the other soap ingredients are well mixed and slightly emulsified.

A mixture with an accelerant is probably not a good choice for swirling or fancy effects.

If you really love an EO or FO that accelerates trace, consider making the soap with hot process technique instead of cold process.

Be especially careful when you work with trace accelerants. It's possible for undissolved lye to remain in the mixture. Look at your soap critically, and test any "different" areas with pH paper, NOT WITH YOUR TONGUE OR FINGERS. Don't touch your soap until you've tested it. Look at the exterior of a soap log carefully before slicing, and test at different spots on the exterior. Look at the faces of the slices just as carefully. If you have individual bars, look all of them over thoroughly, and test any areas that look different.

Bay Laurel—I love bay leaves in food and love the essential oil in soap. But it is a fierce trace accelerant, and it's necessary to use every trick I know to make soap successfully with it. It's only worth it to take so much trouble for a real favorite.

What Would I Do?

If I wanted to use a trace-accelerating FO or EO in a soap, I'd do some or all of the following.

Work cold.

Increase liquid to 35% of fats rather than my typical 30%.

Avoid other ingredients such as sugars that tend to accelerate trace.

Use a silicone block mold.

Add the accelerant after pouring the soap mixture into the mold.

Cool the soap after pouring.